Revisiting the RIBA Collections: Plas Newydd and the Ladies of Llangollen

Revisiting the Collections is a blog series inviting people working to amplify underrepresented voices in the cultural and built environment sectors to share their reflections on materials in the RIBA Collections. Through this series, we hope to enhance the collective understanding of our collections, forge fresh collaborations, and tell new stories about the history of architecture.

In this piece, chair of RIBA’s internal LGBTQ+ Community group, Emily Jeffers explores how a cottage in rural Wales has led contemporary historians to re-evaluate how we project our own understanding of female queer relationships onto historic figures, particularly women, who have expressed intimacy in different ways.

Situated on the outskirts of Llangollen in north Wales, is the former home of Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby. Now a tourist attraction, the Grade II* listed cottage was where Eleanor and Sarah called home for over 50 years, known as their ‘retirement’.

Affectionately labeled the Ladies of Llangollen, Eleanor and Sarah’s relationship has caused much speculation about whether they were more than just friendly roommates.

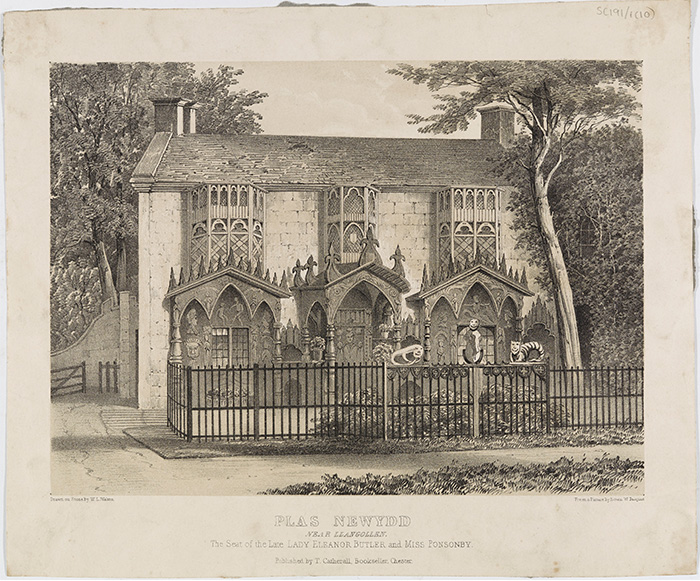

Choosing to abandon conventional lives in their native Ireland, Lady Eleanor Butler (1739-1829) and Sarah Ponsonby (1755-1831) rented a small cottage in Llangollen called Pen-y-maes around 1780, where they spent the rest of their lives as an intimate couple. The cottage was renamed Plas Newydd (‘new mansion’ in Welsh) and was redecorated in the Gothic style by the pair between 1780 and 1829.

They would go on to build a library, extra room, service rooms and a cellar as well as remodelling the front of the building before buying more land to expand further. This land eventually covered ten acres of grounds including rose gardens and a woodland extending to the Cyflymen stream.

In 1819, Sarah and Eleanor were able to purchase Plas Newydd “by which time they had become absorbed in the collection of oak carving which was brought to them by many of their famous guests such as Charles Darwin”. The oak carving panelled interior consisted of these ‘gifts’ by guests as well as many more, older than the house itself, that had come from local churches being remodelled during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Romantic female friendships were not uncommon in 18th century Europe, and the language frequently used between them could often be interpreted as overly passionate, similar to a sexual relationship. This intimacy for some could be attributed to the fact that many women of higher social classes would not work and therefore spent a lot of time in each other’s company entertaining guests.

While there is no definitive proof that Eleanor and Sarah were a couple, they often called each other “my better half” and shared a bed. This was also not uncommon for women of the time, but it raises a bigger question: Are female romantic relationships today considered less ‘serious’ than their male counterparts because of the way women throughout history have openly expressed their affection for each other, in romance and friendship?

Despite these types of female relationships being considered commonplace for the period, the Ladies of Llangollen must have been somewhat unique, as they drew the curiosity and company of people like William Wordsworth, Percy Shelley, Sir Walter Scott, Josiah Wedgewood and even Anne Lister who was no stranger to sapphic social circles herself.

Anne was especially fascinated by the pair, likely because they demonstrated that two women could live together in their own home, away from the duties and restrictions of being a man’s wife.

During one of her visits, “Anne tried to discreetly establish whether Sarah Ponsonby and Eleanor Butler were more than friends. She asked ‘if they were classical’ to which Sarah Ponsonby replied, ‘No…Thank God from Latin & Greek I am free’.”

In a letter to one of her lovers, Mariana Lawton, Anne shared her thoughts on the pair. “I cannot help thinking that surely it was not platonic. Heaven forgive me, but I look within myself & doubt. I feel the infirmity of our nature & hesitate to pronounce such attachments uncemented by something more tender still than friendship”.

The romantic activities of these couples may be similar on the surface to those of the present day, but the lens from which these relationships would be labelled, is not. During Eleanor and Sarah’s lifetime, any speculations about their relationship, in print and by word of mouth were not met with definitive confirmation about their life in the bedroom. This may simply be because the way they behaved publicly did not differ enormously from their female peers.

While there is still profound value in platonic friendship, amongst all genders, downplaying these types of female relationships where evidence suggests, erases the historical knowledge that women’s sexual identities can exist beyond a proximity to men and the need to bear children.

There is something optimistic about the idea that women throughout history have chosen to live their lives amongst friends as an alternative to nuclear family life. But due to this ambiguity, same-sex desire has often gone unrecorded throughout history, leading to a false narrative that it simply didn’t exist until the late 20th century.

Expressions of love have never been bound by gender or sexual identity and Plas Newydd serves as a perfect example of how four walls can provide a space for endless possibilities when it comes to female relationships.

Learn more about LGBTQ+ materials in our RIBA Collections with the OUT of Space exhibition currently on display at the RIBA Library and in our LGBTQ+ spaces research guide.

Read more stories inspired by the RIBA Collections, or browse RIBApix for 100,000+ digital images of our historic collections.