A Tale of Two Towers: Trellick Tower turns 50

Between 1965 and 1972, two striking new residential towers rose to the east and west of the London skyline. Both were designed by the Hungarian architect Erno Goldfinger, and both were part of a wider movement to replenish unsanitary and depleted housing stock in the decades following the Second World War.

The first of the two buildings, Balfron Tower, was in the east London neighbourhood of Poplar. Once it was finished, Goldfinger and his wife Ursula moved in for two months to learn from the building’s successes and limitations, as well as publicly making the case for high-rise construction. It was a canny PR move that attracted media curiosity, especially the drinks parties the couple threw in their flat for their neighbors.

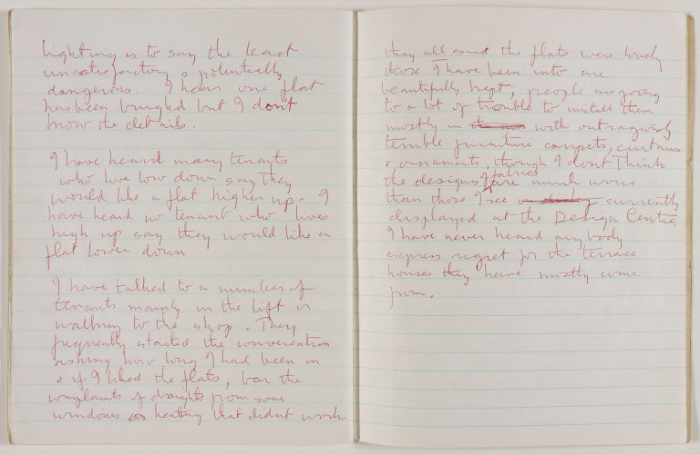

Ursula Goldfinger’s notebooks from this period, held in the RIBA Collections, reveal some of the findings they noted during the stay. The lighting was, she wrote, “to say the least unsatisfactory and potentially dangerous.” A common complaint was the dearth of lifts, of which there were only two. But the Goldfingers were encouraged in the tenants’ attitudes towards high-rise living. Ursula wrote that she had heard “many tenants who live low down say they would like a flat further up – I have heard no tenant who lives high up say they would like a flat lower down”.

So, when Goldfinger turned his attention to west London he was confident his efforts in Poplar could offer a blueprint, with a little fine tuning. The resulting Trellick Tower, Balfron’s sister to the west in Kensal Rise, officially opened 50 years ago, on 28 June 1972.

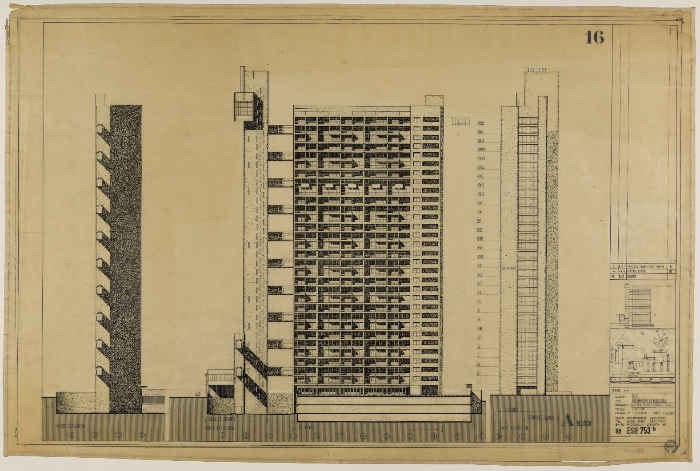

At 31 storeys, Trellick stood even taller; Goldfinger saw high-rise construction as key to retaining ground space for amenities and children’s play areas. The tower formed part of the Cheltenham Estate, a mix of low and high-rise buildings combining new homes with shops, a nursery, and other facilities to create a mixed community. The tower’s distinctive silhouette, with a separate service tower linked to the main block through a raised walkway at every third level, was now a tried and tested format. This time, Goldfinger rotated the service block by 90 degrees, and added an adjoining seven-storey block. The addition of four extra storeys to the main tower gave Trellick a slenderer appearance than the more bulky looking Balfron.

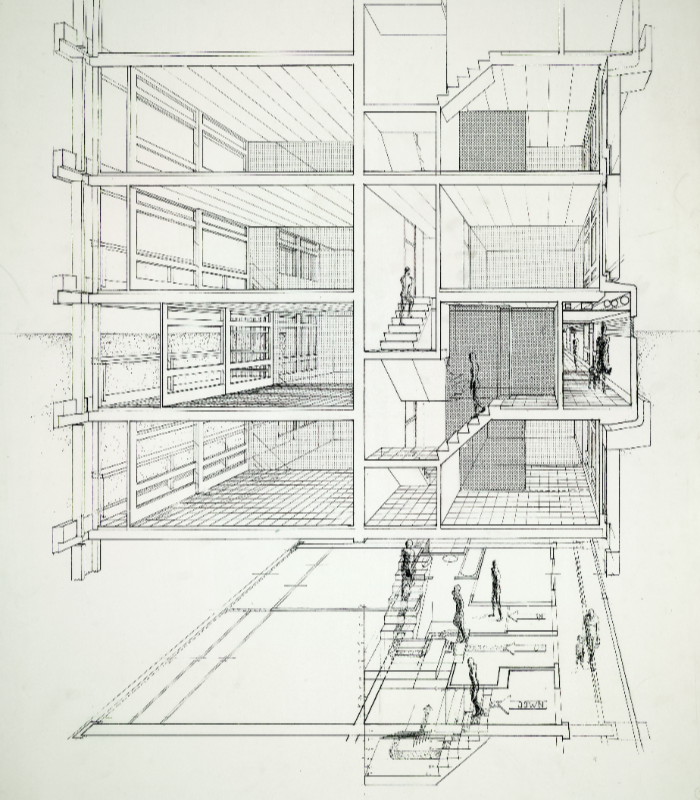

Inside were 271 homes, mostly one and two-bedroom flats alongside five two-storey maisonettes. The flats were thoughtfully arranged to ensure each home had a balcony off its living room. From the exterior, these balconies contributed to the tower’s distinctive façade. A presentation section drawing from 1962 illustrates how the homes were accessed and some of their features, including the balcony access, sliding doors, and timber-framed windows. Light switches were integrated into the apartments’ doorframes.

Today, Trellick Tower’s legacy is complex. The Brutalist design has been revered as a meticulously detailed exercise in high-rise living and social optimism, and reviled as a failed socialist experiment blighted by poor maintenance and crime. Brutalism’s return to fashion has come at a cost – some of the flats in Trellick Tower are now on the private market, priced far beyond the means of many of the people the block was originally designed as home to. But the building’s significance as a model of high-rise social housing, and the culmination of Goldfinger’s design philosophy, is now recognised. Its Grade II* listed status has prevented its signature hammered concrete façade from being clad, which some have argued might have resulted in a tragic fire like the one at Grenfell Tower five years ago.

In 2021, the Kensington and Chelsea Council shelved plans to redevelop the estate, following resistance from residents and heritage groups who objected to the proposed loss of children’s play spaces and graffiti wall, alongside other amenities. Half a century after Trellick Tower opened, its next 50 years are hotly contested.

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*):

- Robert Elwall, ‘Erno Goldfinger’ (London: Academy Editions in collaboration with the Royal Institute of British Architects, 1996)

- Elain Harwood, ‘Space, Hope and Brutalism’ (Yale University Press, 2014)

- Historic England, ‘Trellick Tower, Cheltenham Estate, Golborne Road’ (National Heritage List for England)*

- Paul Hyett, ‘Trellick Tower: a giant among high rises’ (Architects’ Journal, vol. 209, no. 18, May 1999)

- Stefi Orazi, ‘Modernist estates: the buildings and the people who live in them today’ (London: Frances Lincoln, 2015)

- Alan Powers, ‘Modern: the Modern Movement in Britain’ (London: Merrell, 2005)

- RIBA, ‘The Architecture of Modern Play’ (Google Arts & Culture)*

- Rob Sharp, ‘Battle commences over McAslan plans for Trellick redevelopment’ (Architects’ Journal, vol. 221, no. 12, March 2005)

- Nigel Warburton, ‘Erno Goldfinger: the life of an architect’ (London: Routledge, 2003)

- Trellick and Balfron Towers were also the subject of a recent exhibition in Milan, co-curated by RIBA's Valeria Carullo and drawing on material in the RIBA Collections.