RIBA’s fourth commission in the Architecture Gallery, Disappear Here: On perspective and other kinds of space, explores the lineage of perspective across centuries and technologies.

Connecting the disciplines of art, architecture and mathematics, the exhibition highlights the difference between reality and how we represent it through new architectural installations, an animated film, original drawings and rare books from RIBA’s Collections.

RIBA’s commissions are an opportunity for emerging and established practices and artists to work with RIBA curators to explore its historical collections through a contemporary lens. For this project, RIBA commissioned Sam Jacob Studio to transform the gallery into a mesmerising spatial environment on the theme of perspective.

We provide an introduction to the exhibition and to the theme of perspective – where it originated and what the future may hold - interspersed with quotations from Sam Jacob, the principal of Sam Jacob Studio, taken from an accompanying essay.

What is perspective and where does it come from?

Perspective is a method of representing three-dimensional space on a flat surface. It depicts an idea of space that seems to coincide with our understanding of reality. Yet, it is not reality. It is a system, an artificial construct, that manipulates and distorts our visual perception while enabling accessible and popular representation of a design in three dimensions.

The depiction of space has a long and wide-reaching history as Sam Jacob writes in the accompanying essay to the exhibition:

'If we scan a history of how space has been drawn, either as representation of the world or as architectural proposition, we see just how fluid and varied conceptions of space have been …from, say, Neolithic cave paintings through medieval maps, Byzantine paintings, Asian handscrolls to Google Maps we see how different worldviews are codified through representation. We see space itself shifting like a camera pulling focus.'

Perspective was evidenced and formalised in the Italian Renaissance, but of course existed long before this era. Vitruvius, who published the first architectural treatise 'Ten Books of Architecture', credits the painter Agatharchus (fifth century BC) with knowledge of perspective when designing stage sets. However, it was Leon Battista Alberti in 'De pictura' (1435), who first described the principle.

Since then, a number of architects, mathematicians and artists have written extensively on the subject with Sebastiano Serlio being the first architect to dedicate an entire book to perspective in the mid-sixteenth century.

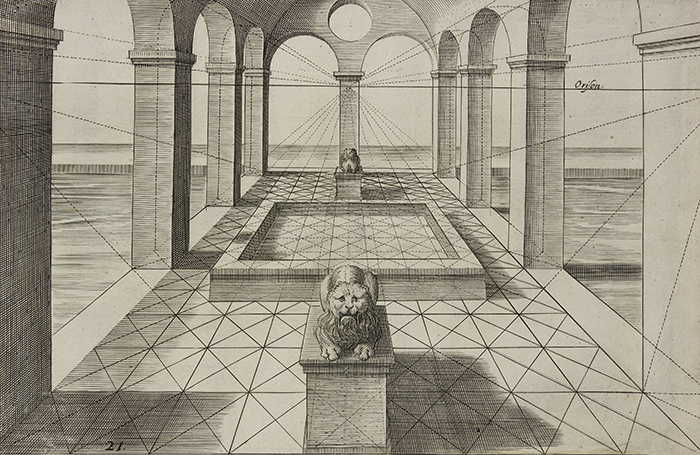

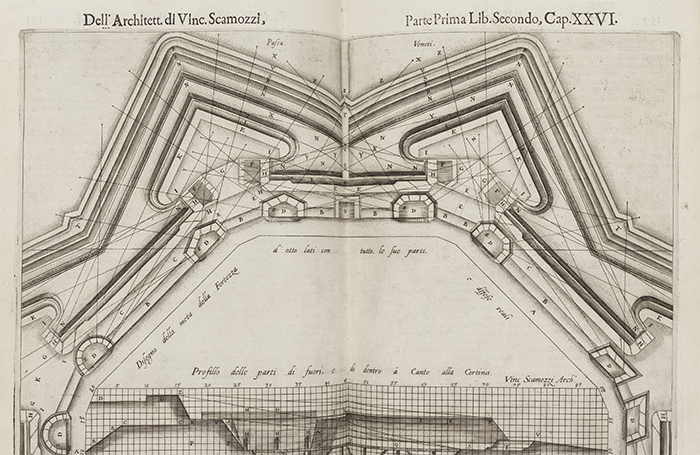

Through clear instructive text accompanied by woodcuts, Serlio explains the basic use of a vanishing point, perspective lines and horizon to draw in three-dimensions. Not long after its usage in depicting and decorating architecture was the technique of perspective deployed by the military and the navy, for topographic surveying, designing fortifications, calculating projectile trajectories and navigation.

The future of perspective

From Google maps to 3D modelling, BIM and virtual reality, the tools used to represent space continue to evolve. We can now visualise, and become part of, a fabricated 3D world. Using the power of the first-person view in virtual reality, we can experience different perspectives within the same environment – whether planning complex urban landscapes or experiencing social interactions.

'Disappear Here' explores this technological framework through a newly commissioned film. In collaboration with video game developer Shedworks, an animation immerses the viewer in a perspectival drawing, where deconstructed objects drawn from Renaissance treatises flow from a distant horizon. Where a painting or drawing positions the viewer in front of the image, this film, with no beginning or end, places the viewer within a perspective image.

But drawing remains a fundamental representative technique, recently taking on a graphic quality, where collage is at once digital and hand drawn, rendered and etched. This May, hear from the architecture practices who are redefining this post-digital form of architectural representation, using drawing to communicate the social, cultural and political environments of their projects.

Using the RIBA Collections

Disappear is informed by the RIBA’s vast Collections, one of the largest and most diverse architectural collections in the world.

Sam Jacob: 'The drawings from the collection span hundreds of years, drawn by very different authors, of very different subjects at varied scales. We see in them the constant assertion of perspectivity: Grids, converging lines and vanishing points. Hung so that the logics of perspective cross the boundaries of the frames they suggest the convention of perspective shapes far more than just the drawing itself. Perspective is the space in which the drawings – and the architecture that they propose – occur.'

This unique wall hang according to the logic of vanishing points and perspective lines provides the viewer with their own unique perspective on artwork by some of the most talented designers in history.

Visit architecture.com/DisappearHere for more information on the exhibition and our programme of events, or visit RIBAPix for our Disappear Here image selection.