Liverpool School of Architecture, Abercromby Square

The Liverpool School of Architecture building was completed in 1933 to designs by Charles Reilly, Lionel Budden, and James Ernest Marshall, following funding from Viscount Leverhulme.

Among the vast, well-known buildings pictured on the mural of the Jarvis Hall at 66 Portland Place, London is a more modest-looking one that few will recognise. Just to the left of the Bank of England and the Palace of Westminster, you’ll find the painting of an austere, flat-roofed, and boxy brick building.

This building is part of the School of Architecture at the University of Liverpool, located in Abercromby Square. It was completed in 1933 to designs by architects Charles Reilly, Lionel Budden, and James Ernest Marshall.

Despite appearances, this modernist building perhaps has more in common with the terraced houses surrounding most of Abercromby Square than you might think. As a port city in the northwest of England, much of Liverpool’s architecture was shaped significantly by its role in transatlantic commerce.

In different ways, both the School of Architecture extension and the earlier terrace to which it was attached, were constructed with the proceeds of colonial trade. Number 19 Abercromby Square was originally commissioned in 1862 by American cotton merchant Charles Prioleau as his Liverpool residence. Over 60 years later, its extension, built for the School of Architecture, was funded by Viscount Leverhulme, whose family money came from the firm Lever Brothers, a major soap manufacturer founded in the nearby town of Warrington. The firm sourced palm oil from the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) and Solomon Islands, and traded extensively in British West Africa through numerous subsidiaries. The company later became Unilever.

William Hesketh Lever, 1st Viscount Leverhulme, aspired to become an architect as a young man and was later awarded Fellowship of the RIBA. This interest in architecture extended to his role in supervising the planning of Port Sunlight, the model village the Wirral Peninsula, Merseyside built to house employees of the Lever Brothers soap factory.

Lever later compared Port Sunlight to Lusanga (then ‘Leverville’), built for the Lever Brothers’ subsidiary in the Belgian Congo. In both locations, Lever claimed to have improved the lives of workers and their communities through the offer of paid labour, but in the Belgian Congo employees (many of whom were forcibly recruited) faced a punitive regime of extremely low wages, poor living conditions in barracks-style housing, and harsh labour. In Port Sunlight, workers experienced better treatment. Lever was a proponent of shorter working days and co-partnership, but the supposed benefits of employment with the company came with certain caveats. Lever touted a profit-sharing scheme, but invested profits into the town rather than directly distributing them, on the basis that employees supposedly did not have the moral values to spend the funds wisely.

When Lever died in 1925, he left funds to the University of Liverpool for the refurbishment and extension of the Abercromby Square building to which the school would be relocated. Lever already had a longstanding interest in Reilly and the university. Reilly had designed some houses in Port Sunlight around 1905, and Lever had funded the establishment of a Department of Civic Design, of which Reilly was chairman. Appealing to Lever for the endowment to set up this department, Reilly had pointed out the virtues of town planning at Port Sunlight.

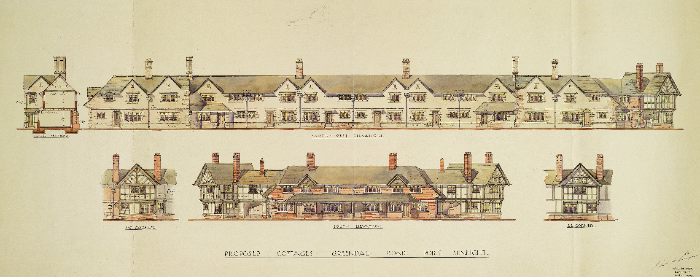

The new School of Architecture building was a long time coming; Viscount Leverhulme had first promised the funds before the First World War. In the meantime, the school had experienced a nomadic couple of decades, and in the 1920s was housed in an unsuitable former hospital building in Ashton Street nicknamed ‘Reilly’s Cowsheds’. Reilly drew up designs alongside his fellow faculty members (and former students) James Ernest Marshall and Lionel Budden. The resulting extension was faced in brick in deference to the neighbouring houses, and contained the school’s bright and simple studio and workshop spaces. Its central courtyard had been earmarked to a house a Doric column, salvaged from the demolished Liverpool School for the Blind, as a “symbol of architecture and of permanent architectural values”. Despite its modernist new accommodation, the Liverpool School of Architecture was associated during Reilly’s tenure with teaching architecture in the classical style.

So why was this modest looking university premises featured alongside the parliamentary and administrative buildings on the Jarvis Hall mural?

Alongside his role as chairman of the school and his involvement in the design of the new building, Reilly was also a member of the RIBA Council (represented at the centre of the mural) and served as the institute's Vice President in 1931. The RIBA’s new headquarters building opened in 1934, just a year after the new School of Architecture. Other council members’ designs also feature on the mural, such as Herbert Baker’s Union Buildings in Pretoria, which alongside his and Edwin Lutyens’ projects in New Delhi, also featured, would have been among the best-known imperial buildings. The link to Viscount Leverhulme, after whom the building was named, perhaps meant the school building represented to the RIBA a symbol not only of national architectural relevance but also international significance.

The building’s inclusion in the mural also reveals something about the RIBA’s aspirations for the future of British architecture. Back in 1894, Liverpool’s introduction of a degree course in architecture had offered one of the first routes into the profession for aspiring architects who could not afford to pay to be articled to a practice. The school became a backdrop to the emergence of architecture as a regulated profession that required formal educational routes. When Reilly took the helm in 1904, he set about raising the school’s significance nationally, working with the RIBA's Board of Architectural Education to secure its status as the UK’s highest profile architecture school. His ambitions for the architectural profession went beyond the walls of the School of Architecture. The establishment of the Department of Civic Design was part of his ambition to bring the disciplines of town planning and architecture closer together.

Today, the 'Leverhulme' Building is among the buildings whose legacies are under increased scrutiny because of their links to colonial exploitation, and the University of Liverpool has announced plans for a new naming framework for its buildings. Meanwhile, a new extension designed by O'Donnell and Tuomey is currently under construction, for which the 1930s corner building served as an important reference.

The Liverpool School of Architecture's inclusion alongside colonial government buildings on the Jarvis mural serves as a reminder of the role of attitudes towards empire in the development of the architectural profession in the UK, and reveals the surprising link between a university building, a quaint-looking model village in present-day Merseyside, and an exploitative company town in the former Belgian Congo.

Find out more about symbols of the British Empire in RIBA's buildings and collections.

Further reading (available in the RIBA Library unless marked*)

- Michael Hall, ‘Life with Lord Leverhulme’, Country Life vol. 195, no. 24 (2001)

- Benoît Henriet, ‘Hubris and Colonial Capitalism in a Company Town: The Case of Leverville 1911-1940'*

- William Hesketh Lever, ‘The Six-Hour Day & Other Industrial Questions’ (London: Allen & Unwin, 1918)

- Charles Herbert Reilly, ‘Representative Architects of the Present Day’ (London: Batsford, 1931)

- Jules Marchal, 'Lord Leverhulme’s Ghosts: Colonial Exploitation in the Congo' (London: Verso Books, 2008)*

- Peter Richmond, ‘Marketing Modernisms: The Architecture and Influence of Charles Reilly’ (Liverpool University Press, 2001)

- Joseph Sharples, ‘Charles Reilly and the Liverpool School of Architecture 1904-1933’ (Liverpool University Press, 1996)

- University of Liverpool, ‘School of Architecture History: The World in One School’

- University of Liverpool, 'Building Mercantile West Africa' Project, investigating the architectural and urban legacies of Lever Bros and Unilever’s African subsidiaries (publication of this research is forthcoming).

- Myles Wright, 'Lord Leverhulme's unknown venture: the Lever Chair and the beginnings of town and regional planning, 1908-48' (London: Hutchinson Benham, 1982)